Scrub Revolution

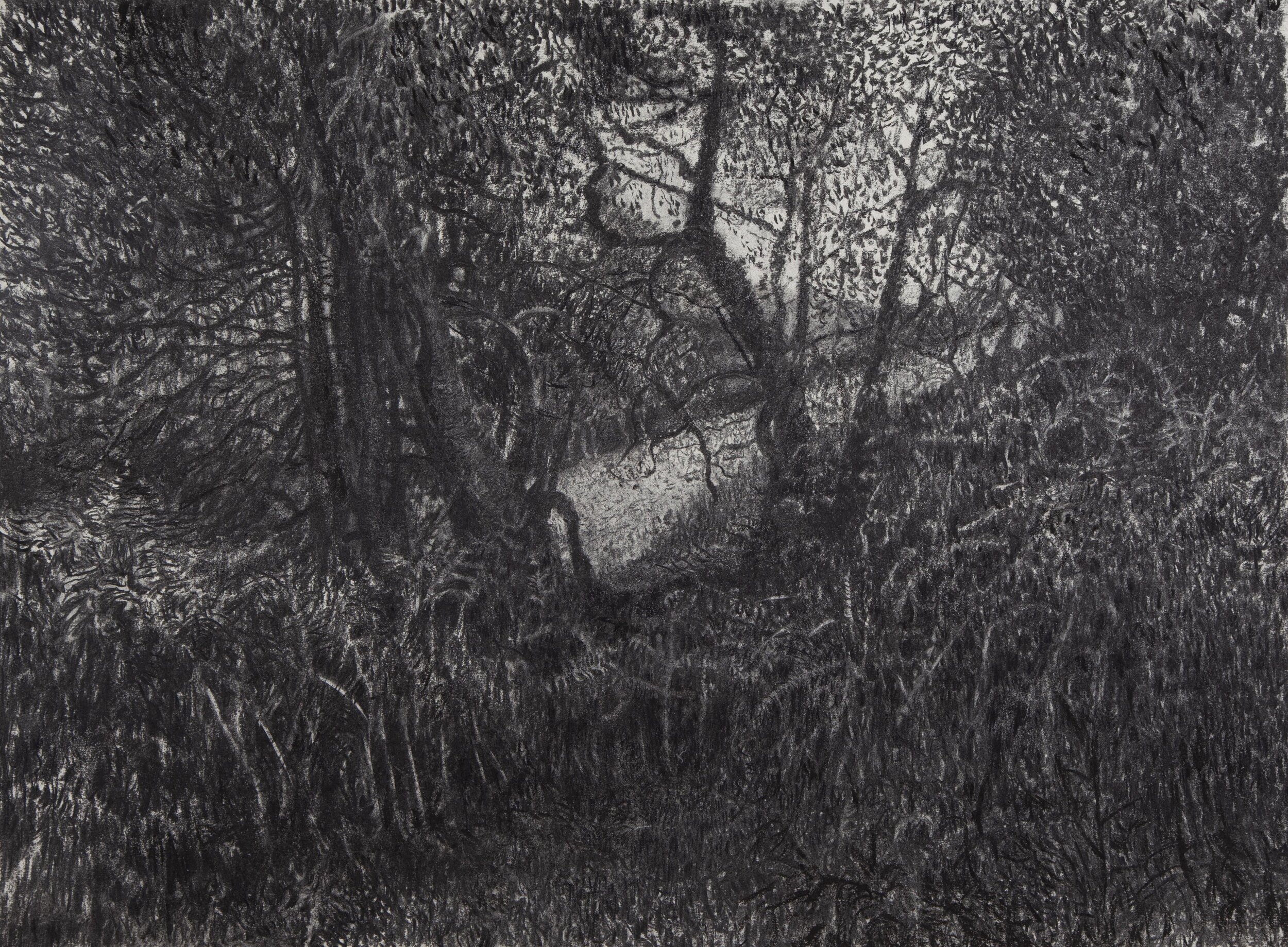

Dartmoor Scrub - Clare Tyler (charcoal on paper)

SCRUB REVOLUTION by Clare Tyler

When I read “Wilding” by Isabella Tree I felt that I had come home.

I was mesmerised by this inspiring account of the pioneering rewilding project at the Knepp Estate in Sussex and the powerful possibilities it presents for our planet in its state of cataclysmic decline of nature.

I also felt a resonance with its basic principles on a very personal level.

All my life I have felt and been drawn to scruffy! I love soft verges, the earthy surface of old lanes, sedge grassed meadows, the surge of wayside flowers. Restored furniture, patched up buildings and chipped ceramics all speak to me of long appreciated functional alliances. I often relish the considered use of unusual repair materials as adding creative appeal to the original object - I rejoiced at my friend Steve’s kind surgery of a broken 1950’s chair, transplanting a ‘wooden leg’ from a Victorian seatless wreck.

My lovely mum tried in earnest to remedy my teenage shabbiness with smartening up trips to Country Casuals, but they were in vain. Although I could appreciate the beauty of well designed fabrics and fashion I always felt more comfortable with clothes that were well loved, mended and lived in. Eventually she gave up putting my old boots in the dustbin when she saw my commitment to these old friends by a polish or a resole, but I often felt her disapproving anxiety that I might be bringing shame onto our Surrey home.

And as for cars...give me a dented or scratched and modest one any day. I can only imagine the stress suffered by the drivers of gleaming and generous of breadth motors as they navigate the lanes of Devon where I now live.

My cottage garden is a tumbled riot of wild and domestic flowers. It throbs with life, feeding the insects and bullfinches, yielding herbs for tea and remedies. I only cut the tiny lawn now and again as I love to see the spangled dishevelment of dandelions and daisies, trefoil and speedwell in the grass, providing nourishment to the bumble bees and butterflies.

Yet from somewhere in the recesses of my suburban childhood clangs a critical bell..”Perhaps your lack of neatness and control will be judged as laziness, incompetence or even reveal lack of self esteem.”

Similar criticisms also were aimed at Isabella and Charlie as they proceeded with their extraordinary experiment. Their bold decision to stand back and let nature do what it knows best threatened the views of local farmers who were concerned about the far reaching consequences of the emerging natural species.

Isabella writes with compassion about these concerns and now with time, as the wilding proved itself to not be spreading with negative consequences into the neighbouring fields, there is less resistance to the project and more appreciation for the shared increase of birdlife and pollinating insects.

But it was her understanding of some of the more deep rooted psychology behind the need to look tidy and be busy that really spoke to me.

After the War, she writes, Britain was verging on bankruptcy. With much of Europe starving, dependants in her protectorates to feed and little to export or import, there was less food than during the war itself. Food rationing continued until 1954 and the notion of feeding ourselves became more than just a matter of security. The energy for the Dig for Victory campaign which had ploughed or dug up much of the land, including commons, cricket grounds and the South Downs, continued with incentivised enthusiasm. Peak production became the driver and all land was seen as potential to its purpose. Any fallow land was considered wasted land and untidiness was deemed almost immoral.

Ultimately this honourable dedication to ensure Britain would never go hungry, has created the landscapes which we have become used to today, disguised as the green and pleasant land. In truth they are often industrial deserts- lack of crop rotation endowed with herbicide and fertiliser, destroying the balance of ecosystems vital to our survival and that of the planet. (Today, we already over produce enough food to feed eleven billion people and 40% of the world's food production is wasted.)

Hedgerows ripped up, water meadows drained, ancient forests felled..the list goes on and in its wake a land so devastated with its nature declining in a continuing dropping base line which we sadly have come to accept as normal.

However this particular time in history only marks a certain point of how the British countryside has become a factory. Many scientists recognise how nature has come under human control with the result of significant natural habitat decline, commencing way back with the start of the Industrial Revolution around 1760.

The first few chapters of Benedict MacDonald’s illuminating and visionary book “Rebirding” make for depressing reading by detailing these losses as they come decade after decade, but it is vital for us to understand what has happened if we want to find ways to remedy the situation.

“To restore our wildlife, we must remember what was ours. Only by doing so can we hope to bring it back-in a more educated and enlightened age.” Benedict Macdonald (the Anthropocene, Rebirding)

The book is however ultimately optimistic, giving passionate and authoritative solutions to how we can turn things around.

For me, the crucial need to generate treasuring of the unordered land began to fuel my work as an artist. I felt inspired to make work to try and change some attitudes of aesthetics of untidiness and instead encourage a cherishing of its more subtle beauty and value.

For some time I have been immersed in drawing the scruffy and overlooked land at the back of my cottage. I feel more in love with this rebellious area as I observe it over the weeks and months and prize its beauty of intertwining tangle of holly, rowan, sycamore, hazel, hawthorn, blackthorn more keenly than any grandiose parkland. The ground is covered in flower speckled coarse grasses, nettles, brambles, gorse and bracken buzzing with insects. The trees and blackthorn hedges throng with birds; chiffchaffs, blackcaps, willow warblers. In May I am accompanied by the calls of a cuckoo and his bubbling wife, while nightjars churr from the moorland edge on warm summer evenings.

Benedict MacDonald writes with energy about the need to recognise the powerful profusion of nature in such land in the chapter, “Ecological Tidiness Disorder.” He feels that the urge to cleanse and tidy (a very British compulsion) has become an alarming obsession for councils and our own. As he sees no economic reason to spend taxpayers money to prevent natural life in our towns or roadsides, he asks us to re value our actions in order to protect the habitats of beloved species like hedgehogs which need the scruffy harbours of wood piles and undergrowth to survive.

He writes, “ Is that untidy bush, chippering with sparrows, overgrown? Or is it just a bush? If you have a rural garden, is that ivy an indicator that you’re not in control - or is it the home of a spotted flycatcher? That muddy ‘waste ground’ down the road may be the only place a house martin can find building supplies. Is that loose tile a social disgrace - or an opportunity for a swift?”

Continuing my reading of “Wilding”, I learnt about the rich fertile secrets of scrub. I read with fascination about the nurturing aspects of the thorny plants that create nurseries for the oak trees; the acorns planted by jays.

Isabella describes scrub as ‘ one of the richest natural habitats on the planet’

“...scrub produces a wealth of margins for wildflowers and invertebrates, particularly those with complex life cycles that require two or more habitats close to each other for different stages in their growth. Invertebrates attract other invertebrates and small mammals, amphibians and reptiles, which in turn attract birds and other predators.’ (Isabella Tree, “Creating a Mess, Wilding”)

And yet because it seems unproductive, this precious type of habitat, home to beloved species like nightingales and willow tits, brimstone and white letter hairstreak butterflies, sloe carpet and figure of eight moths, is sadly deemed as wasteland and almost entirely eradicated in Britain through the destruction of areas like hedgerows and margins, brownfield sites and even nature reserves. The numbers tell the devastating effects; nightingales have declined by 90% since the 1970s and willow tits have declined by 88% between 1970 and 2006, becoming our fastest vanishing birds.

Furthermore, Isabella’s recount of the definition of scrub struck a chord in me that had a deep, almost psychological reverberation which, although I appreciate could feel a little disturbing to some people, suggested a disobedient but positive force.

“Scrub, by definition, is habitat on the move. In the absence of grazers and browsers it is vegetation on the way to becoming closed canopy woodlands..Scrub doesn’t stand still. The more you cut it down, the more prolific it becomes. Even defining it is difficult and mapping it virtually impossible..it is endlessly morphing, on its way to being something else – a discomforting notion to the modern mind.’

My brother Paul ( a keen birdman) and I began to discuss further analogies of this fertile habitat. Perhaps a metaphorical sense of wilding ourselves is required, letting our own personal creativity scrub generate and infiltrate our own lives?

For a while Paul had been considering the possibly ironic consequences of the garden makeover programmes of the 90’s. He wondered if the measures to help express gardeners’ identities with things like decking, bark chipping, metal or plastic edged curved lawns, removed the ‘mess’ that later was recognised to aid nature; probably the very thing they were hankering after to nurture their souls.

As a professional in the business coaching world (Handling Ideas), Paul has much experience with the power of process. He has created a successful mapping approach that enables creative thinkers to get their concepts out of their heads and onto a table using lego. Complicated stories can unravel and the complex relationships between characters are freshly explored and wrestled with, crafted and allowed to become something else. He even suggested formats for business that could grow out of an understanding of scrub, especially for the Arts. What seemed obvious is that it had deep reaching connections with the creative process.

This wayfaring into creative territories reminded me of an exhibition I had experienced a couple of years ago in Devon, “Dreaming with Open Eyes’ created by artists Selby McCreery and Alice Clough.

The exhibition was an invitation to participate in a whole (graceful and unkempt) Georgian house, barn and garden installation of materials and found objects and multimedia practices to ‘excavate what lies beyond the visible, traces, impressions, articulations”.

Selby condensed her inspiration for the work in these words,

“If we see birth as a miracle- the process of becoming as a holy act; in being alive, we are always in process- always emerging, responding, dynamic in relation to elements and stimuli. At this time, where increasingly we lean in to weigh, to number, to measure and to map, we need wild spaces, both materially and psychologically, as a vital bridge to reimagine and re-sacralise the way we choose to live and inhabit.”

People wandered, relaxed and quietly absorbed, around the airy rooms; some taking part by rearranging the materials or drawing and writing in notebooks, harnessing the effects of the permission to let go of control and inhibition and instead pathway into the realms of imagination and memory. It was simple and gentle, yet the atmosphere was incredible and I felt deeply moved for days.

In a similar thread, last year, encouraged by my daughters I undertook the “Artist's Way” by Julia Cameron. Described as “a spiritual path to Higher Creativities” the book covers a twelve week course designed to help people connect with their creative energies, by encouraging the removal of blocks and nurturing confidence. Filled with activities that encourage” letting go” and “getting out of the way” it reminded me of the basic tenets of Wilding. A poignant example being the core practise of the Morning Pages, a daily delve into spontaneous or automatic writing.

For me, this early morning exercise often started with a repeat of the phrase “I don’t know what to write,” but began to meander into long, untouched parts of my subconscious memory, up- turning revelations and excavating depths of personal understanding that I found emotional and enriching.

I felt I was wandering and exploring in a kind of inner scrubland and although there were plenty of difficult thorny places to navigate I was becoming entranced by encountering my personal versions of nightingales, fritillaries and dog rose.

I returned to the real life Scrub and began to draw again. Up to now my focus had been in observation, drawing what I could see. But now I let myself feel more into the actual place, imagining it form an arena for images from my imagination to occupy.

I had always admired the work of artists and poets who had this natural freedom to let their imaginations spill onto the page. Artists like Blake and Picasso, poets like Lorca, Rilke and Emily Dickinson. Before I had found it difficult to break through my inhibitions and have the same trust of my creativity that I had experienced in early childhood. Being immersed in Scrub was proving to nurture a part of me that longed and then began to break through with tendrilled growth.

As my personal creative journey evolves, it is accompanied by a new mission...to encourage a Scrub Revolution, not only to raise awareness of the importance of protecting and encouraging the return of this most precious habitat but also as a way of activating our creative potential as humans.

Let us examine and console our fear of the unknown so often displayed by the habits of control:

usefulness, constant doing, making good, fixing, cleaning, sterilizing, ordering, tidying, arranging, problem solving, sorting and managing…

and instead give space for our resonance with healing, our connection with each other and with nature through,

pausing, listening, allowing, leaving, nurturing, forgiving, observing, resting, opening.

One of the wonderful, hopeful things about the nature of scrub is that it is always ready and waiting to find spaces to creep back in. Take time to notice its presence in the weeds that grow in the cracks in the pavement, in the margins and rough areas in towns and country alike (Summer nights in Berlin are graced by the song of Nightingales who return each year to the city’s scrubland).

If you can and have not already, do read the two re-wilding books mentioned as they are both gloriously scripted and give extraordinary amounts of information and thoughtful vision of ways we can begin to encourage nature back.

And if you have a garden or some land, give a corner over to the glorious tangle and take some moments everyday to pause and watch what comes to spend time there. You might be amazed by the richness it yields for nature and for yourself.

Scrubland

by Steve Guthrie

Throughout the year, from grey and brown, red and white

And back again the growing, shrinking, dying back of interminable

Convoluted threads,

Sometimes soft but often spiky webs.

Of passageways,

Not subterranean but of the ground

Thriving, enlivening, yet in time

quietly burying the path makers

The secret comings and goings,

the haven- the final lair

Where hunter and hunted make their secret trysts

Away from prying eyes.

Where leaves, thorns and rare blossoms transcend their

Lowly settlement and bind the Earthen Kingdom

in mysterious entanglements

The almost bush the nearly tree

Scrubland

Holly hedge - Clare Tyler (charcoal on paper)

Books mentioned

Wilding The return of nature to a British Farm - Isabella Tree ( Picador)

Rebirding Restoring Britain’s Wildlife - Benedict MacDonald (Pelagic Publishing)

The Artist’s Way -Julia Cameron (Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam A member of Penguin Putnam Inc)